The Washington Standard newspaper reported in its November 12, 1897 edition that “It’s raining pitchforks with saw logs for handles and the tines downward.” In other words, the weather was typically wet for that time of year in our part of the country. What caught my eye though in that issue of the paper was a reference to Tumwater: “Tumwater Park received an unexpected accession to its population the other day, in the shape of a baby elk, which was born in the park from a captive elk.” Keep in mind that this was around 65 years before our modern day Tumwater Falls Park was constructed on the same site in 1962 in time for the Seattle World’s Fair.

I’d read some references to that early version of a park with a Northwest Trek kind of theme and even saw some photos of it, so seeing that old article inspired me to look a little deeper into Tumwater Park and how and why it was developed. I found that it was closely related to what was happening to the industry along the Deschutes River at the turn of the century and the transition that was taking place from water-powered mills to water-driven electric power generating.

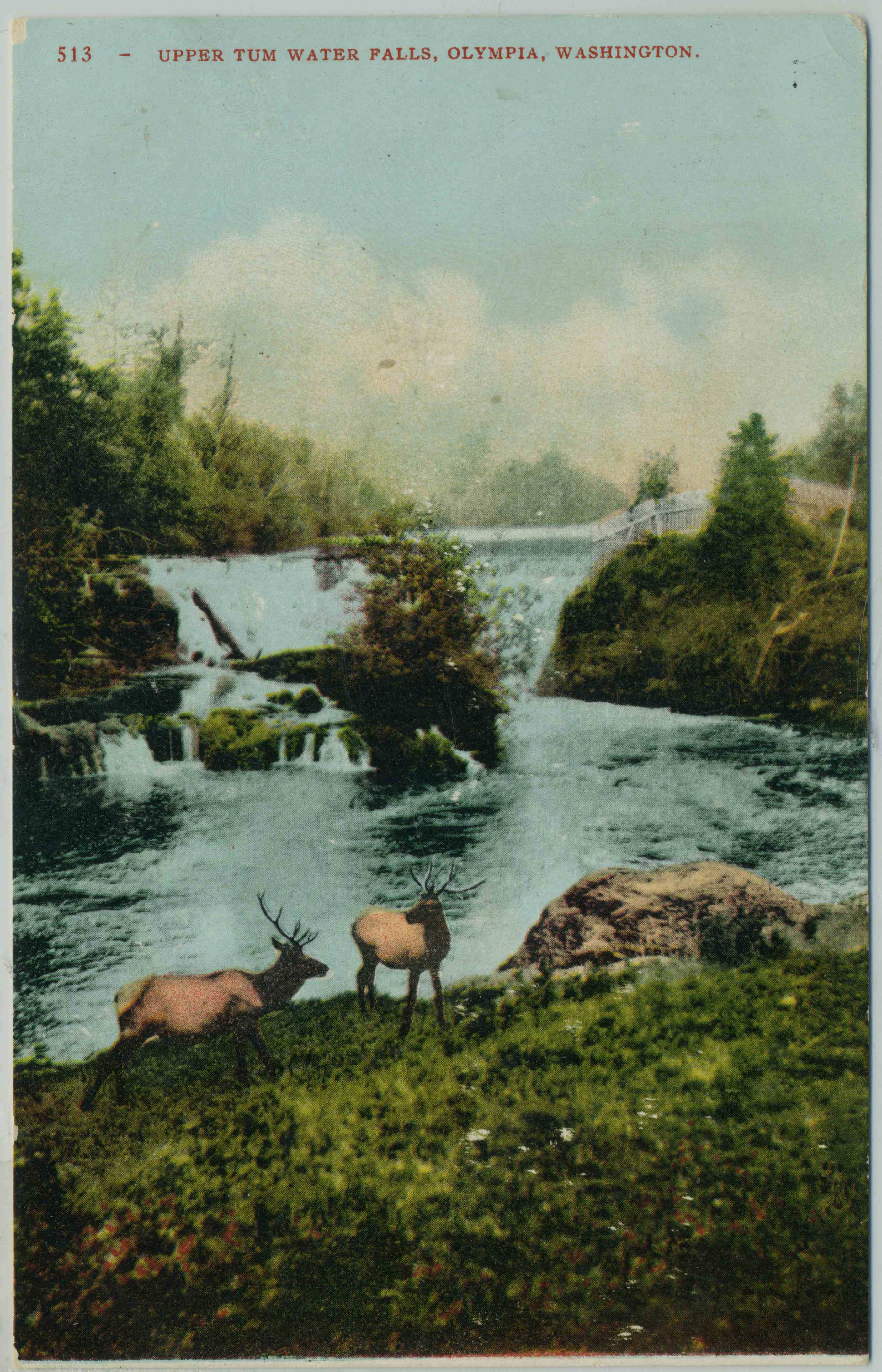

At the time of our statehood in 1889, the Washington Standard and its publisher John Miller Murphy said that Olympia considered Tumwater Falls its greatest asset as it provided the best water power in western Washington. This was a time of great advancements in technology, as well as a time of excitement and business growth due to our attaining statehood. With Olympia the new state capitol, aspiring business people scrambled to land various kinds of franchises for telephones, street railways, water systems, gas lights, and electric power systems. In fact, in that same year Olympia Light and Power Company got the franchise for provision of electric power to Olympia and Tumwater along with the right to operate an electric street railway, or streetcar, which since 1884 had consisted only of horse-drawn trolleys. Their power generating site was on the middle falls of the Deschutes next to the Gelbach flour mill. In May 1890 the company bought the Gelbach flour mill for $10,000 and built a dam to provide more water to generate the needed electricity. By 1892 they began to produce power, which included the streetcar system from downtown Olympia all the way to Tumwater. The end of the line was the east end of the Boston Street Bridge. One of the corporate owners, Hazard Stevens, the son of our first territorial Governor Isaac Stevens, was inspired to create an animal park to draw citizens of Olympia, with their picnic lunches and families, to the end of the line in Tumwater.

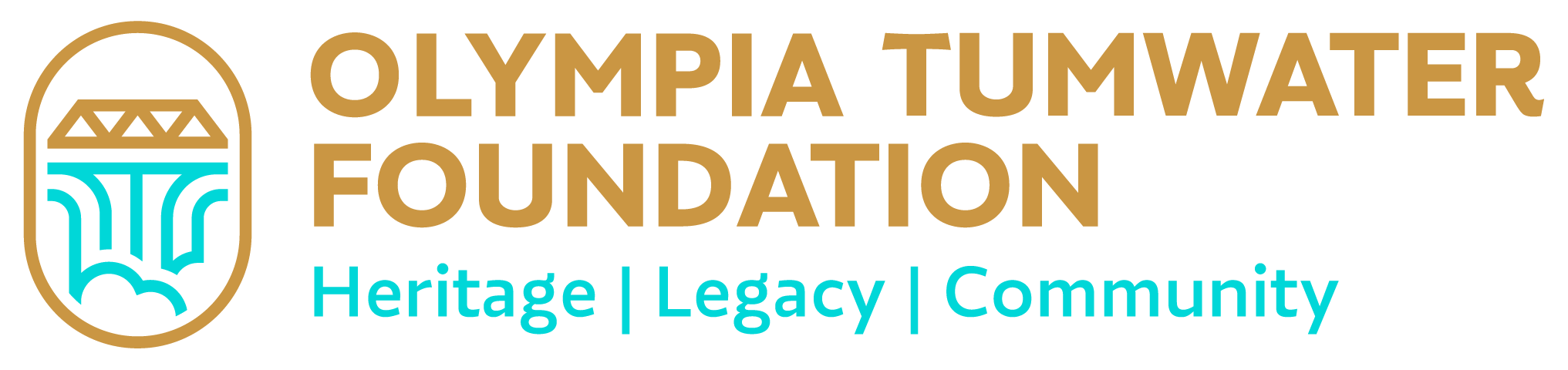

A short article in the Washington Standard from November 4, 1898 made another reference to the park, saying “Two of the elk family which have been living a life of ease in Tumwater Park have been purchased by Eastern parties and shipped to New York.” The elk were a major draw for visitors, but that wasn’t the only wildlife featured. In August 1900, another article described the blasting of the river bed and the dam being built for the new flume for the power plant. The article stated, “This section of the river has been the undisputed habitat of the swans since their importation. What disposition will be made of those noble birds remains to be seen; but they will probably be assigned to that portion of the river which meanders through the company’s elk range above the first fall. Much to the disgust of their ursine majesties, the bear pit has also been invaded to make room for the new channel.”

It’s quite apparent from the press coverage of the day that the care of the wildlife in Tumwater Park was not without incident. The April 17, 1903 issue of the Washington Standard printed, “One of the swans in Tumwater Park was killed by an elk the other day, which all at once developed murderous proclivities. The swan was swimming near the shore of the DesChutes which passes through the park, when the animal jumped upon it, inflicting injuries from which it soon died.” On April 1, 1904, the paper covered a confrontation between animal and human: “In returning one of the bears in Tumwater Park to the enclosure from which he had escaped Tuesday, Arthur Dye was severely bitten by the brute, and R. F. Nichols, a watchman in the yards of the Northern Pacific Railway likewise suffered from the teeth of the enraged animal. A posse of citizens went after him, who still showed fight, and a rifle had to be brought into requisition to subdue his wild spirit. The remedy, however, resulted in the death of the bruin.”

I found one more reference to Tumwater Park in that newspaper, which appeared a month later in the May 27, 1904 issue. It shows that the animals weren’t the only attraction developed to draw visitors from Olympia: “Wright’s Band played in Tumwater Park Sunday evening, to the great delight of residents of that village and many people from this city.” It’s nice to know that the roots for our wonderful Falls Park of today run so much deeper than I first imagined. Now the main animal attraction here is the salmon run up the fish ladders in the fall. The traditions continue.

Nov. 2015, Don Trosper